After the Ends: Another 24-hour Cold War Film Screening

2006/2012

Orchestrated as a 24-hour film exhibition, After the Ends is a screening of post-apocalyptic films from the Cold War period. Each film imagines the aftermath of some global disaster, particularly those that are man-made, which free the inhabitants of those worlds to pursue their true desires, unfettered by the norms and structures of common society. The screening as a whole is a reflection on the Cold War anxiety of mutual destruction and the liberatory elements of a society begun a new, with the loss of society comes the loss of its restrictions and repressions. Each film is an imagining of a possible world, and each film testifies to the cultural imaginary at work at the time they were made, i.e. what the fears and fantasies of unfettered freedom might look like. The structure of the whole film program is akin to a skipping record, viewers watch the world reborn over and over again as it progresses. As a 24-hour screening, it has been presented at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (as part of Walead Beshty: EMBASSY! a dismal science waiting room, 2006); lnstitut im Glaspavillon, Berlin (2006); ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe (as part of Between Two Deaths, 2007); the Kadist Foundation, Paris (as part of The Backroom, 2007); the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (as part of the 2008 Biennial Exhibition); Thomas Dane Gallery, London (as part of Walead Beshty: Travel Pictures, 2012); and The Power Station, Dallas (as part of Walead Beshty: Fair Use, 2013). The film program is accompanied by comprehensive screening notes provided to the audience and reproduced below.

Beginning in 2012 with the screening at Thomas Dane Gallery, the work is shown in two parts: the first is shown as the previous iterations have been, and the second is shown in reverse.

Titling Convention:

The date attributed to the work is the year of its first exhibition. Here, the second date is added to reflect the second part of the screening in reverse. A final description of the work, for example one that would appear on a wall didactic in an exhibition space, might read:

The Continuous Presents of Past Futures (Post-Apocalypses 1959–1985), )5891–9591 sespylacopA-tsoP( serutuF tsaP fo stneserP suounitnoC ehT

The Continuous Presents of Futures Past (Post-Apocalypses 1985–1959), )9591–5891 sespylacopA-tsoP( tsaP serutuF fo stneserP suounitnoC ehT

2006/2012

Fifteen commercial films from the Cold War era, color offset print, Apple Mac Mini, and wireless headphones

films: 48:00:00, color, sound

poster: 46 ¾ x 33 1/8 inches (118.9 x 84.1 cm)

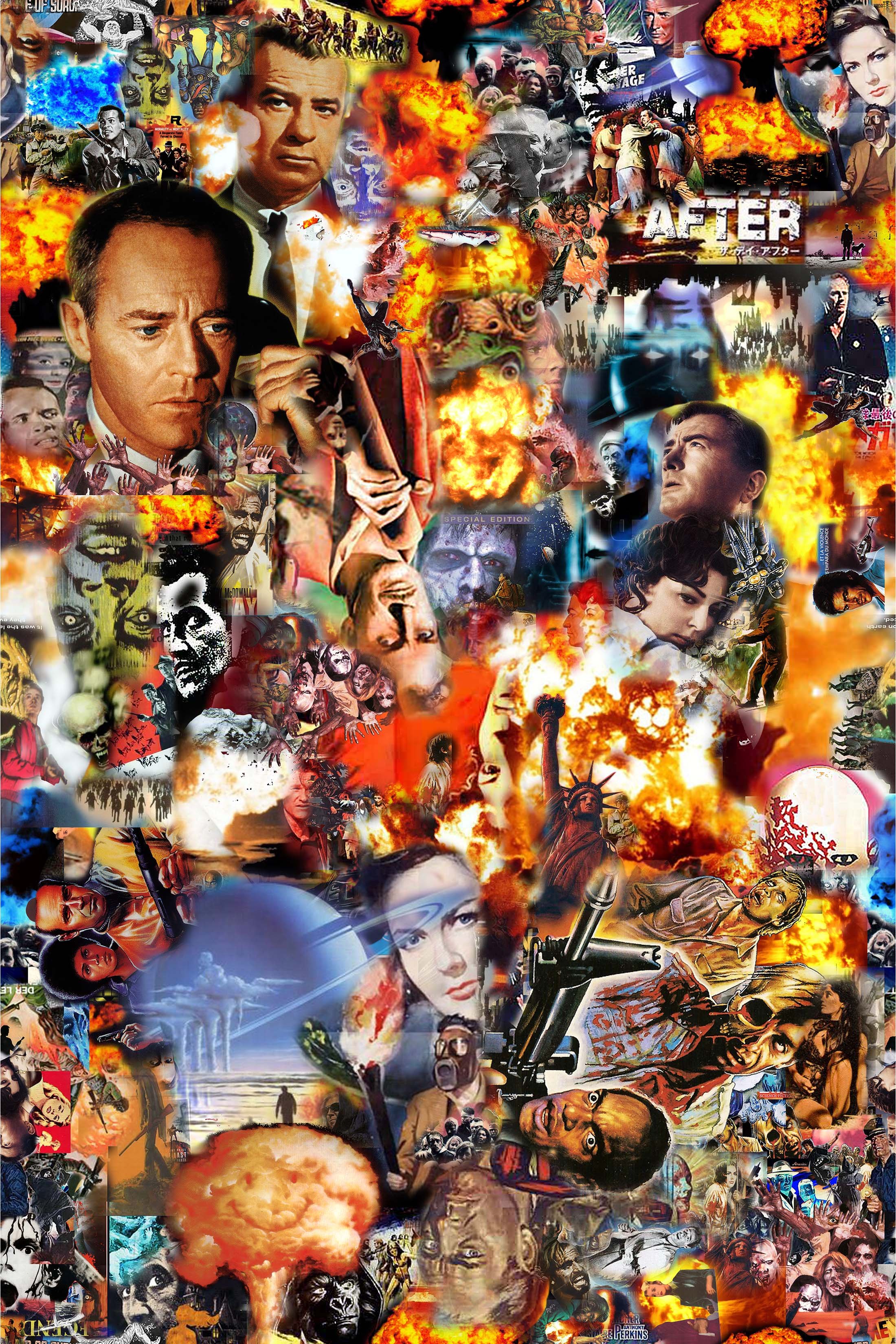

The work is accompanied by a lithographic print of a collage drawn from posters of post-apocalyptic films from the Cold War era. The collage poster is designed to be endlessly repeatable when hung in multiples, a decorative analog of the reliving of the end of society ad infinitum. It can be adapted to fill any space, just as the screening itself is able to be adapted to any location.

After the Ends: Another 24-hour Cold War Film Screening Notes

The World, the Flesh and the Devil

1959, Ronald MacDougal, 95 min.

'The most unusual story ever told!"

Harry Belafonte stars as a miner who by happenstance (he is trapped in a coal mine) misses the total destruction of the human race. In this neutron bomb-like imagining of the end of the world, we follow Belafonte while he wanders the streets of New York looking for other survivors. Unique in the genre for its strong racial undercurrents, and its beautifully shot scenes of an evacuated lower Manhattan, the film draws heavily on the novel The Purple Cloud (1901) by M.P. Shiel, George R. Stewart’s The Earth Abides (1949), and Ferdinand Reyher's The End of the World (1951), who was a close friend of Brecht and shared some of his beliefs on the role of populist entertainment to change societal inequities. While the method of the destruction of the world is clearly borrowed from Shiel, the hubris of his protagonist is substituted with the humanism of Stewart’s narrative. Early iterations of the literary genre, most notably J.A. Mitchell's The Last American (1893), have distinctly Malthusian racialist thematics (this is also the case in Shiel). While The World, the Flesh and the Devil makes special attempts to reconstitute and restructure the racial metaphors that were so deeply implied in the “survivor” narratives and provides an allegorical warning to a culture that threatens to destroy itself both socially and technologically.

Panic in Year Zero!

1962, Ray Milland, 93 min.

“An orgy of looting and lust!”

"An orgy of looting and lust!" was perhaps too strong a tagline for this largely conventional yet telling narrative of a nuclear family weathering a nuclear attack on Los Angeles. Moral proclamations pervade, as the primary unit or moral order, the patriarchal family, is the last hope for surviving catastrophe. Frankie Avalon completes the cast as a loveably misguided teenager under the tutelage of his father, a moral purist and self-reliant figure, a joe-everyman turned superman. As is often the case, the true danger comes after the bomb in the form of a moral and ethical collapse embodied most clearly in the teen ruffians who taunt, threaten, and brutalize our heroes.

Fail Safe

1964, Sidney Lumet, 112 min.

A technical malfunction leads the US and the USSR to the brink of war, despite every effort to avert the disaster. A blatantly humanist film, Lumet speaks of the alienation of powers that be–to the point of their not having any control over their own machines–from the realities of war. Characters act out their struggles in blank offices, and control rooms filled with machines, and even when the ultimate disaster occurs. Destruction is represented by mechanical tone instead of special effects. Even in this moment of reckoning, the horrors of nuclear war can only exist as an abstraction.

The Last Man on Earth

1964, Ubaldo Ragona, 86 min.

“Do you dare imagine what it would be like to be the last man on earth... Or the last woman?”

The first film adaptation of Richard Matheson's I Am Legend (1954), The Last Man on Earth follows the book more closely than the more popular The Omega Man, actually having had Matheson work on the script. Richard Morgan (played by Vincent Price) is a distinctly melancholic figure, a scientist survivor who mourns the death of his family as he kills the undead and heaps their bodies into a smoldering trash pit. The film was shot in a suburban section of Rome called the EUR (the Exposition Universale Roma), built by the architect Marcello Piacentini who was commissioned by Mussolini to produce a monumental site for the 1941 World’s Fair, which also provided a backdrop for Michelangelo Antonioni's 1962 allegory of disaffection The Eclipse (the black poodle in Last Man on Earth is a possible homage to the Antonioni film). To this day the EUR contains a museum of Italian heritage, complete with scale models of the Roman Empire under Constantine. Its opening was delayed until 1942, for the 20-year anniversary of the fascist regime, yet never fulfilled its original purpose due to the escalation of World War II. For the majority of the film, Morgan accumulates a massive body count of the groaning, almost mindless zombies who linger by his home at night droning his name with impunity. But these are less a threat than the highly organized sect of young zombies Morgan confronts in the conclusion of the film, who, with the help of a serum, have retained the ability to organize, operate vehicles, and wield conventional weapons. More militia-like than undead mob, their uniformly black dress is a thinly veiled reference to the fascist paramilitary "Black Shirts." Morgan, skewered by one of their spears after a military style raid on his home, grumbles out his last words in a stupefied tone on the altar of a nearby church, "I am a man ... The Last Man ... they were afraid of me ... Why were they afraid of me?!?" After his sacrifice, the world is able to fully start a new, the last remnant of its old culture left like a pagan offering on the church’s altar.

The War Game

1965, Peter Watkins, 48 min.

Despite having won an Academy Award for Best Documentary, The War Game is fictional. Its grainy handheld realism and graphic depictions of the effects of nuclear attack were almost too effective, having been deemed too violent and intense to air on BBC1, for which it was intended. War Game's impact as a pseudodocumentary has since been repeatedly imitated, notably by other consciousness raising TV imaginings, such as Threads (1984) and its lighter American counterparts The Day After (1983) and Special Bulletin (1983). The film was a direct response to the British Military's "Project Square Peg," which speculated as to the effects of a Trident missile strike on Britain.

Beneath the Planet of the Apes

1970, Ted Post, 95 min.

"What lies beneath may be the end"

The second in the series of Apes films, this one starring James Franciscus (who bears a striking resemblance to Charlton Heston who starred in the previous film), is on a rescue mission to find the missing astronaut Taylor (Heston). The movie reaches its climax as Franciscus discovers the last of the race of humans. They at first seem to have created a utopian society hidden underground in the remains of the New York City subway, but turn out to be a group of telepathic sociopaths scarred by nuclear war, who spend the majority of their time torturing apes and worshiping a gold nuclear warhead.

The Omega Man

1971, Boris Sagal, 98 min.

“The last man alive is not alone”

Richard Matheson's science fiction classic I Am Legend (one of the first to imagine a world populated by zombie/vampires), provided the inspiration for this film. Neville, played by Charlton Heston, is a renaissance man, a scientist haunted by the communal, post-capitalist, technology-hating throngs of the undead. The symbolic elements of this film, especially when viewed in the context of the late sixties (the "erosion" of traditional values, the prevalence of communes, racial unrest, the civil rights movement, and other political agitation etc.) are writ large, as Heston roams the city hunting down the deindividualized members of the "Family," lead by a former television anchorman. As a heroic fish out of water, Heston represents the moral compass, and cultural values feared to have been lost in the oft-repeated alarmist claims against the student rebellions and civil rights protests of the sixties. Christ metaphors reach their climax as Heston's blood becomes the only hope to save the human race, and he is crucified on a piece of modern art, a monument to advanced cultural taste. Sweeping shots of downtown Los Angeles in a state of postapocalyptic abandon provide another thrill. The film was scheduled for a remake in 1997, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, but was canned because of the cost of depopulating an entire city proved untenable. A similar fate threatened the original but was solved when the producer and director took a Sunday drive through downtown LA and realized it was already empty. Recently, the book was the subject of a third adaptation, this time with Will Smith playing the role of Neville.

A Boy and His Dog

1975, L.Q. Jones, 91 min.

'The year is 2024, a future you'll probably live to see"

A young Don Johnson stars in this post-apocalyptic narrative, set in a world similar to that of the Mad Max series. Originally titled "Psycho Boy and His Killer Dog," Johnson and his telepathic dog hunt for food, and sex. In their journeys, they discover a utopian community underground whose existence is less comforting than it first appeared. Jason Robards makes an appearance as the leader of the community, where the surface of beauty conceals a horrific and repressive society.

Dawn of the Dead

1978, George A. Romero, 126 min.

"When there's no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth"

Following up on Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead follows four characters as they travel the zombie infested landscape and end up in a mall in Monroeville, Pennsylvania. Repeatedly, Romero emphasizes the lack of humanity displayed by the human characters, and has commented extensively on the revolutionary undercurrent of this film, stating, "They're basically blue-collar monsters and they've always represented change," making the mall an appropriate staging ground for his expansive follow up (as one of his characters states, "This was an important place in their lives.") Also based upon Matheson's influential novel, Romero continues the tradition of seeing the zombie/vampire infestation as a metaphor for the changing culture and revolutionary shifts in society. Yet here, the characteristics that the lone surviving humans maintain are anything but noble, and the new world represented by the zombies is not only inevitable, but perhaps, more just: a potent dose of Rust Belt Marxism.

The Day After

1983, Nicholas Meyer, 126 min.

"Apocalypse ... The end of the familiar ... The beginning of the end ... "

Taking place in a small town in Kansas, The Day After follows "average folk" as they cope with nuclear holocaust. Jason Robards, Steve Guttenberg, and John Lithgow provide lovely vehicles through which to experience radiation sickness and psychic distress.

Special Bulletin

1983, Edward Zwick, 103 min.

“We Interrupt this program for the following...”

Filmed as a mock newscast and aired on TV, Special Bulletin details the hijacking of nuclear weapons by radical left "green" terrorists. Acting skills are put to their limits, as the characters enact solemn self-reflection behind the anchor desk.

Night of the Comet

1984, Thom Eberhardt, 95 min.

“The last time it came the dinosaurs disappeared”

This campy offering tells the story of two teenagers who wake up one day to find the entire population of Los Angeles was turned to dust by a comet. The few remaining inhabitants, hideously affected by the comet's "fallout" have become flesh eating zombies, and the teenagers, along with a new-found friend and love interest, battle for survival against a perverse group of military scientists, and the undead throngs. The film is equal parts Valley Girl (1983) and Night of the Living Dead (1968).

Threads

1984, Mick Jackson, 110 min.

“The closest you'll ever want to come to nuclear war”

Threads takes place in the working-class city of Sheffield, England. In the style of the working-class dramatic serial East Enders, the film begins with a slowly paced narrative of daily life. As we get to know our characters, we hear the background chatter of TV and radio detailing the coming conflict between the US and the USSR over their annexation of Iran as a Soviet satellite country. What at first seems like a subplot takes center stage, as the bombs drop, and horror ensues. We follow the main characters through to 20 years after the attack, where the world has returned to Medieval times. Far less friendly than its American counterpart The Day After (1983).

The Quiet Earth

1985, Geoff Murphy, 91 min.

“The end of the world is just the beginning"

This somber Kiwi contribution to the genre follows a man who wakes up after the end of civilization. People have miraculously disappeared from the earth, an allusion to the neutron bomb. Armageddon is repeated, the film taking place between the initial destruction of nearly all human life, and the final destruction of reality itself; truly thoughtful, and self-aware in its execution. An unofficial remake of The World, the Flesh, and The Devil, with a distinctly less upbeat conclusion, The Quiet Earth proffers a listless expression of its protagonists in between the collapse of the societal order which separated them (thus drawing them together) and the literal eradication of all evidence of past culture.